We (And Our Ancestors)

Yom Kippur, teshuva, and the healing of our family line.

According to the Gemara in Masechet Yoma, one phrase stands out as the ikar vidui, the centerpiece of our communal confession on Yom Kippur. One who doesn’t say this line hasn’t fulfilled their obligations for the day. This key phrase is: aval anachnu chatanu, “but we have sinned.”

Here’s the full text from our tefillah:

There’s something unusual here: an extra word. While the version in the Gemara is aval anachnu chatanu, “but we have sinned,” the version commonly said today is aval anachnu v’avoteinu chatanu, “but we and our ancestors have sinned.”

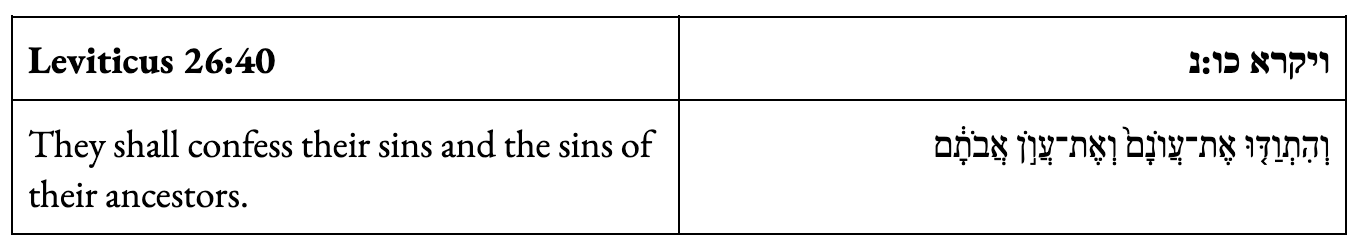

There seems to be a clear biblical origin for this practice. God commands the Jewish people to confess not only their own sins, but also the sins of their ancestors.

Nonetheless, the inclusion of the word avoteinu, “our ancestors”, in our Yom Kippur prayers is relatively recent. While the Rambam uses the word in his account of the liturgy, the Shulchan Aruch, our definitive legal code from the 16th century, doesn’t include the word avoteinu at all. By the 19th century, Jewish communities were divided, with only some mentioning avoteinu. That’s why the word is found in parentheses in some machzorim.

The spread of this practice raises a critical question: how can we, as individuals, be held responsible for the sins of previous generations?

In Masechet Brachot, the Rabbis claim that we are held responsible for our ancestors' sins whenever we are actively holding onto them.

There are two primary ways that we “hold onto” the deeds of our ancestors. First, Jewish law teaches us that we cannot willingly benefit from the misdeeds of previous generations. Children are required to repay the debts of their parents. A person who inherits a stolen good is obligated to return it. The young person, of course, didn’t commit any theft themselves. Nonetheless, they are prohibited from materially benefitting from the moral failings of previous generations. They have the responsibility to make things right.

The second way we hold onto the sins of previous generations is by failing to question the culture we were born into. The Beit HaLevi explains that, in many cases, we subconsciously inherit patterns of bad behaviour from our families. Because this way of living is all we’ve ever known -- we didn’t choose to act this way -- we often make excuses for ourselves. On Yom Kippur, he teaches, we confess for the sins of our ancestors to wake ourselves from this slumber; we have to change our ways, even if it feels as familiar and natural to us as the air we breathe.

Rav Adin Even-Yisrael (Steinsaltz) teaches that we don’t just inherit patterns of thought and behaviour from our immediate family; we’re also influenced by our broader culture.

While it can be challenging to inspect the basic assumptions about how we live, taking responsibility for the behaviours and culture that we’ve inherited also empowers us. Our teshuva has the potential to impact everyone around us.

Rav Tzvi Elimelekh Shapira of Dinov teaches:

This teaching casts our prayers on Yom Kippur in a radically hopeful light.

We pray on behalf of anachu v’avoteinu, ourselves and our ancestors, because each of us has a role to play in the chain of history. We have the power to heal our ancestral line, working to finally make things right. We have the power to change the culture we live in, passing on a better world to future generations. We, as a collective, have the power to set the world back on its axis.

As we pray throughout Yom Kippur, may we feel a glimmer of that work happening inside of us. Anachu v’avoteinu. For ourselves and for our ancestors.

G’mar Chatimah Tovah.