Stoking the Coals: Rosh HaShanah

The truth will set you free, but first, it will burn your lips.

This is the D’var Torah I will be sharing on the first day of Rosh HaShanah. I’m publishing it here beforehand so that my loved ones outside of London can read it before chag. For members of my shul, this post is the very definition of a spoiler. Thanks for understanding and shanah tovah!

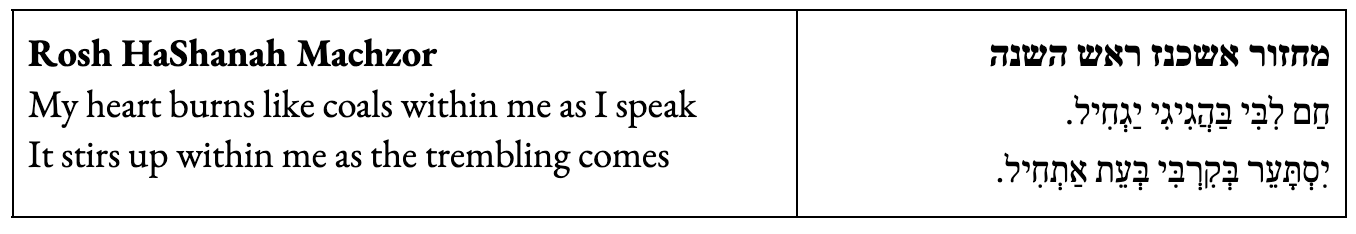

One of the first piyyutim, liturgical poems, of Rosh HaShanah describes the spiritual work of the day as “stoking coals.”

The paytan, Yekutiel ben Moshe, describes the yirah, or awe, of the day, stirring within him. The smoldering coals no longer lay dormant, emitting gentle heat. They’re jolted embers spark and reignite, white hot and burning.

It’s a striking image of what this day demands of us: to stir up the truths that lay buried inside of us, to stoke the coals until we can feel them burn.

During Unetaneh Tokef, we say, “a still, small voice shall be heard.” That gentle voice may be different in each of us: Lingering grief that yearns to be felt fully. Knowledge that we are changing, and that we long for others to see us as we really are. Loneliness. Anguish. Feeling lost.

Isaac Luria, the Arizal, teaches that one is required to cry on Rosh HaShanah. It’s a bit of an enigmatic teaching-- how can we order our tear ducts to cry? My partner, Gabriel, wrote recently about this text in a piece about men letting themselves cry. Rosh HaShanah, he says, is a day where we don’t toughen ourselves up by avoiding hard feelings and putting up walls. We allow ourselves to be stirred by emotion instead of looking away.

We stoke the coals.

Most of us, however, have a part of us that resists. We don’t want to go there, stirring up big emotions and staring into the abyss. And certainly not while standing in a room full of hundreds of other Jews.

There are two figures in Jewish tradition whose stories reflect this collective fear, Moshe Rabbenu, Moses, and the prophet Yishaiyahu, or Isaiah.

The midrash in Shemot Rabbah describes Moshe as a small child. According to the rabbis, the magicians in Egypt received a prophecy that the young Moshe would wrest power from Paroh and urged Paroh to kill the child.

From this moment, Moshe is marked as one who can’t help but turn towards whatever is burning. As a young man, he cannot look away when he sees the overseer beating an Israelite. When he escapes to Midian, the home of his father-in-law, Yitro, Moshe turns towards the burning bush. And, of course, Moshe is the leader that receives the Torah in thunder and flame.

For Moshe, the life of a prophet means being pushed, over and over, to stare into the burning embers. He confronts injustice. He lets himself be transformed by the truth.

But the cost of this is high. Moshe grows up burdened by his burnt, clumsy lips. He’s chronically unable to truly connect and communicate with B’nei Yisrael. Throughout his life, Moshe’s powerful ability to see the truth causes him to struggle with anger, isolation, and the feeling of being misunderstood.

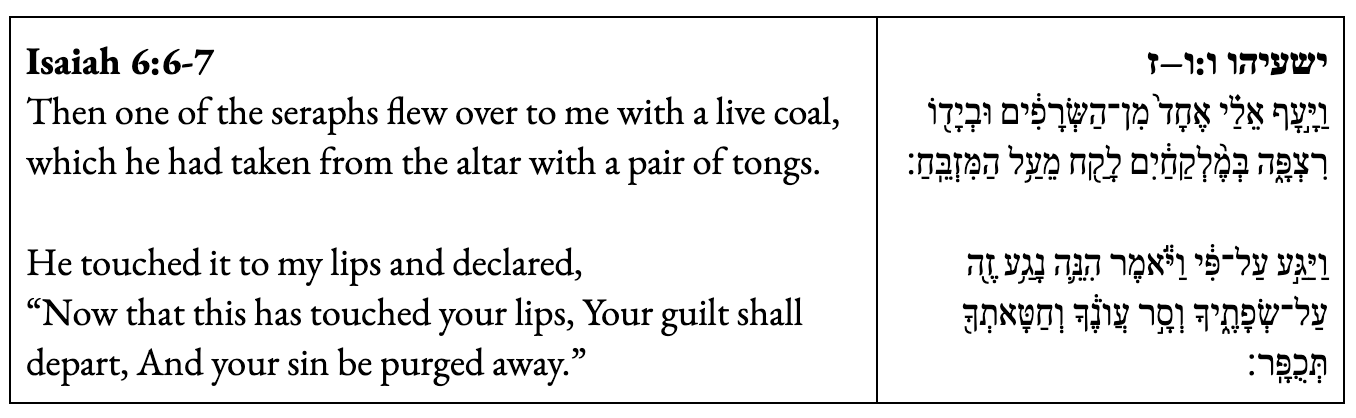

Yeshayahu, whose life as a prophet is filled with similar loneliness, faces a strikingly similar moment.

The Malbim comments on this verse, describing the instant that the coal touches Yeshayahu’s lips as the exact moment that he fully steps into his role as a prophet.

It’s also a moment of kapara, atonement, our central focus of the high holidays. Indeed, a line from this story is found in the Yom Kippur liturgy in some Mizrachi machzorim: “Your guilt shall depart and your sin be purged away.” For Yeshayahu and for us, the burning coals of truth are a source of atonement.

When we say, in our Rosh HaShanah prayers, “my heart burns like coals” we must ask ourselves: What stirs inside of me? What truth flickers in my soul, begging me not to look away?

In “The Cancer Journals,” the pioneering Black feminist writer Audre Lorde writes an intimate account of living with breast cancer and grappling with what she terms “tyrannies of silence”. She writes: “What are the words you do not have yet? What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them, still in silence?”

We must speak these truths, she says, not just for ourselves, but for everyone around us.

“The speaking will get easier and easier. And you will find you have fallen in love with your own vision, which you may never have realized you had. And at last you’ll know with surpassing certainty that only one thing is more frightening than speaking your truth. And that is not speaking.”

This, then, is the work of Rosh HaShanah; to stoke the coals in our hearts. To turn towards the prophetic truth that the Holy One has kindled inside of us even, and perhaps especially, if we fear getting burned.

On Yom Kippur, our Torah reading describes the moment in which the high priest enters the Kodesh haKodashim, the Holy of Holies.

The burning incense fills the innermost chamber of the temple, a place so sacrosanct that the High Priest alone enters it just once per year. Without an altar of burning coals, it would be impossible to draw close to the Divine in this holiest moment of the year.

Each ember that sparks inside of us is precious.

This Rosh HaShanah, our sacred work is to listen for the quiet voice stirring inside of us, stoking the coals and letting them burn.

Shanah Tova U’Metuka.

![Yitro was sitting in their midst and saying to them: ‘This boy has no intelligence. Rather, test him. Bring before him a bowl with gold and a hot coal. If he extends his hand to the gold, he has intelligence and [you should] execute him; and if he extends his hand to the coal, he has no intelligence and he need not be executed.’ Immediately, they brought it before him and he extended his hand to take the gold. The angel Gavriel came and pushed his hand. Moshe seized the coal and placed his hand with the coal into his mouth, and his tongue was burned. From that he became “slow of speech and slow of tongue” (Exodus 4:10). Yitro was sitting in their midst and saying to them: ‘This boy has no intelligence. Rather, test him. Bring before him a bowl with gold and a hot coal. If he extends his hand to the gold, he has intelligence and [you should] execute him; and if he extends his hand to the coal, he has no intelligence and he need not be executed.’ Immediately, they brought it before him and he extended his hand to take the gold. The angel Gavriel came and pushed his hand. Moshe seized the coal and placed his hand with the coal into his mouth, and his tongue was burned. From that he became “slow of speech and slow of tongue” (Exodus 4:10).](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!N4Ev!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fbe1b89db-7eb4-4b6f-82cc-fbfb46d3bf21_1356x714.png)

![And he shall take a pan full of burning coals from upon the altar, from before the HaShem, and both hands' full of fine incense, and bring [it] within the dividing curtain. And he shall take a pan full of burning coals from upon the altar, from before the HaShem, and both hands' full of fine incense, and bring [it] within the dividing curtain.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!aWwL!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fdf433491-c467-4d44-a312-57b5f2571489_1356x308.png)

I loved this Lara. I'll definitely be sharing.